Reading Time: 27 minutesTranscript: Jeff Currie on the Commodities Supercycle – Bloomberg

Transcript: Goldman’s Jeff Currie on the Commodities Supercycle

Back in January, we spoke with Jeff Currie, the Global Head of Commodities Research at Goldman Sachs. At the time, he was bullish on the commodities complex for several reasons. Since then, of course, we’ve seen several markets go on an absolute tear and to a degree that’s taken even him by surpris…

Eugene van den Berg, Oct 2021

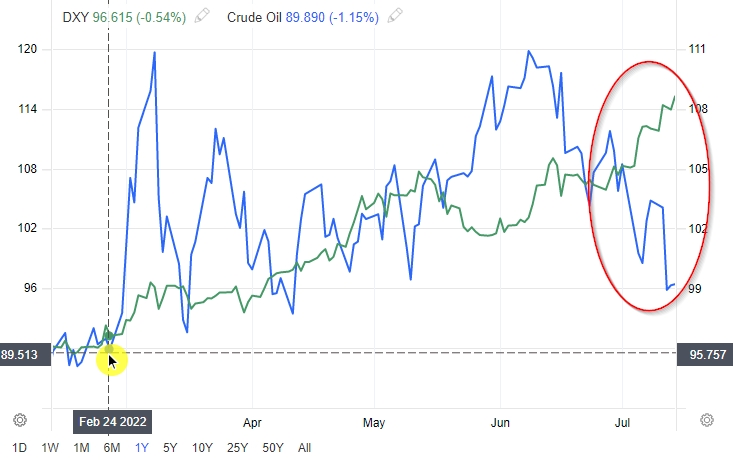

Source: Bloomberg

Back in January, we spoke with Jeff Currie, the Global Head of Commodities Research at Goldman Sachs. At the time, he was bullish on the commodities complex for several reasons. Since then, of course, we’ve seen several markets go on an absolute tear and to a degree that’s taken even him by surprise. The bad news for commodities consumers? We still haven’t hit max pain. On this episode, we speak again with Jeff about what’s driving prices higher and why he sees stronger price increases over the next several months. Transcripts have been lightly edited for clarity.

Hello and welcome to another episode of the Odd Lots podcast. I’m Joe Weisenthal.

Tracy Alloway:

And I’m Tracy Alloway.

Joe:

So Tracy, you see we just got the latest CPI report?

Tracy:

I did indeed. Looks like CPI came in slightly hotter than expected. Like not a huge deviation from the forecast, but of course everyone’s talking about the idea that, well, all of this was supposed to be transitory and yet, you know, here we are almost two years into the global pandemic and it doesn’t seem like any of this is going away.

Joe:

Right. And so, of course, there’s this debate about when transitory means, does it mean pandemic-related or does it mean brief? So we’re starting to split hairs on that. And then there’s also, you know, of course the deviation between headline CPI, which includes energy prices and core, which doesn’t, but the degree to which you could really ever like separate out commodities from the fact that commodities go into everything is kind of impossible. And with the exception of a few things, I mean, we are on a massive commodity/energy bull run.

Tracy:

Yeah. So the crazy thing here is that people were worried about higher inflation even before the commodities market really started going nuts, like just in the past month or so. I mean, I’m looking at some of the energy headlines that have just come over the Bloomberg today and it’s stuff like, you know, European zinc smelters cutting production by as much as 50% because of higher energy costs and, you know, a flood in a major Chinese mine and the Chinese government ending its intervention in the coal market. So basically liberalizing that entire market, which isn’t something that you tend to see that much in China, but is something that is sort of needed given the energy pressures right now. So things have just gotten to a whole new level when it comes to commodities.

Joe:

Yeah. And it’s interesting, you framed that really well. Cause you know, sometimes we do our logistics episodes and one of the themes is the way these sort of pressures compound, right? So something that happens at the port of Los Angeles ends up affecting warehouses, which ends up affecting truckers, which ends up affecting rail at Chicago. And it feels like on the raw commodities front, you see the same thing where it’s like, oh, some energy price spikes. And then the zinc smelters and the fertilizer companies have to pare back production because their production is no longer as profitable. And then that feeds into, you know, some other commodity or something like that. So it feels like there is a similar compounding effect and it’s probably, you know, it seems like a combination of demand, supply obviously. And then there’s sort of like all kinds of idiosyncratic factors, like whether it’s drought or whatever.

Tracy:

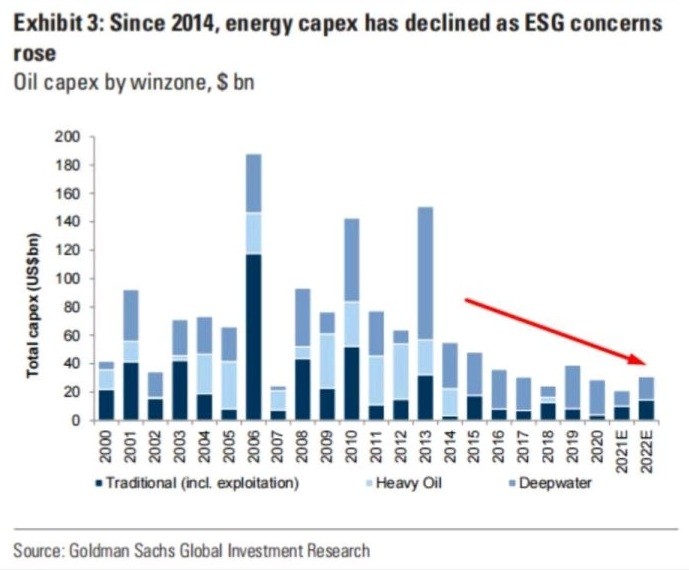

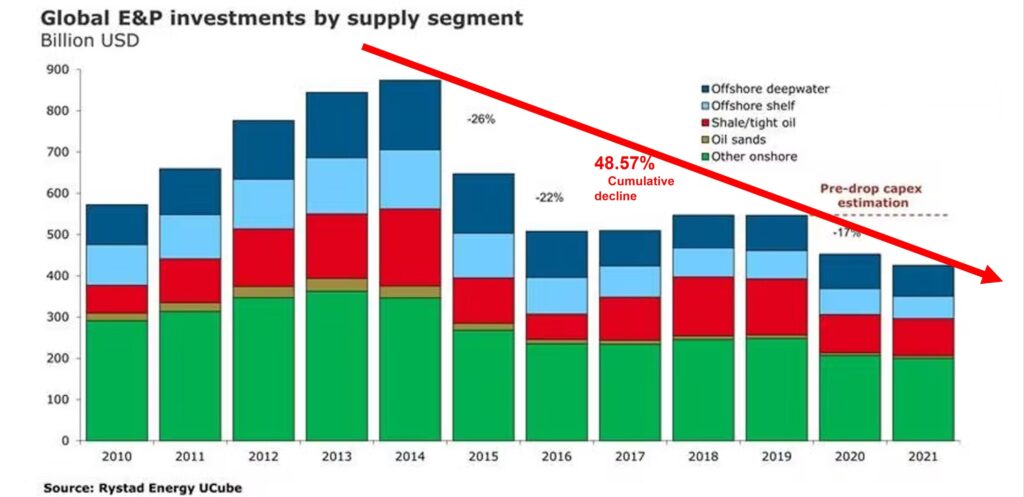

Yeah. Well, the other big thing that people are talking about now is how much of this is caused by the transition to clean energy. So this idea that we’ve had years of structural under investment in traditional fossil fuels, and now we’re sort reaping the consequences of all of that. You know, we don’t have enough renewable energy to satisfy demand just now, but we also don’t have enough traditional fuel. So there is just so much going on in the space.

Joe:

Yeah. And that seems particularly salient in Europe where they sort of pretty aggressively phased down nuclear. And now the natural gas bills are soaring. Anyway…

Tracy:

Wait, wait — I’ve just got to say, now some people are talking about reclassifying nuclear as ESG. So something that would fit under the environmental and social and governance-friendly mantle, which is something that, you know, if you suggested that a few years ago, people would’ve gone absolutely nuts. Anyway, go ahead.

Joe:

Anything to fit anything within ESG is probably like its own story. Anyway, we have the perfect guest on, because not only is he probably the best person to talk about commodities period, but we’ve had them on before. We had them on earlier this year actually in January. And he was very bullish on commodities then. So in addition to being very knowledgeable, yes, exactly. In addition to being extremely knowledgeable, he also has the benefit of having been correct, which a lot of people weren’t. And so now we’ll see what’s next. Excited to bring in our guest. We’re going to be speaking again with Jeff Currie. He is the global head of commodities research at Goldman Sachs, a real treat to have on. Jeff, thank you so much for coming back on Odd Lots!

Jeff Currie:

Great. Pleasure to be here again.

Joe:

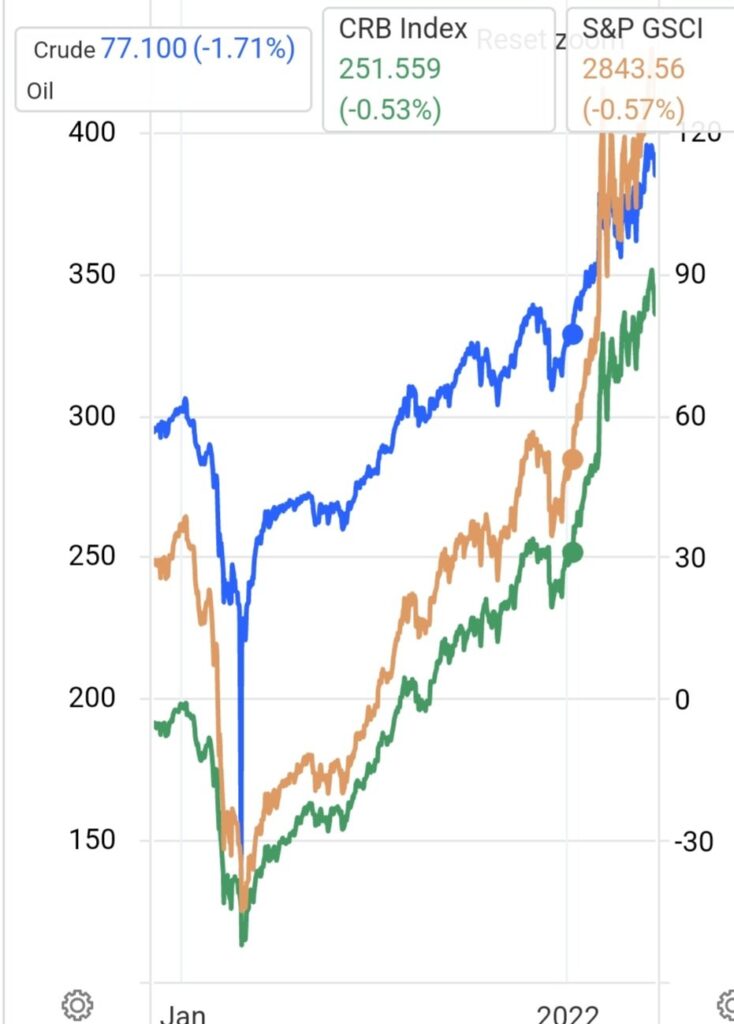

So it’s been, I guess like nine months since we had you on in January and you were sort of, you called it, you were bullish and you said, this is like a big one that you see a big cycle coming. And obviously if you just look at the BCOM, the Bloomberg Commodities Index or numerous other headline measures, that was right. And so what’s your take on what’s happened? How does what happened compared to what you foresaw?

Jeff:

Yeah, it’s far more bullish than, you know, we could have ever envisioned. Let’s take oil. The deficit that we can measure at the end of last month was running somewhere around 4.5 million barrels per day. That’s nearly 5% of the market is in a deficit. That is such a large hole that OPEC the U.S. administration, nobody’s going to fix this. This is like, you know, the train is off the track and you’re watching it in slow motion. But it’s not just oil. You see it in copper, copper inventories dropping 8%, 10% week after week. These are numbers I have never envisioned or never seen before. You know, and you can think about what is going on here. And I think, you know, it goes back to Tracy’s point about that zinc smelter shutting down in Europe. Problems in one market create problems in the other.

So we think about, you know, first it was coal in China, then it became gas in Europe. Then it became aluminum in China, which then impacts copper elsewhere in the world. And it keeps this chain reaction going and each one of these markets get tighter and tighter. So what is it about oil that makes this deficit so much larger than we could have ever envisioned? It’s because you now have oil being used in lieu of both coal and gas because of the shortages in those markets. So bottom line is, you know, we see a lot of up side risk from these price levels, which are far greater than the price levels we were forecasting when we spoke, you know, nine months ago. So bottom line, the underlying picture is far more bullish than what we had expected nine months ago, but the drivers of it are pretty much in line exactly [with] what we thought just in a much larger degree than what we thought.

Tracy:

Yeah. If I could just press on that on this point. So I remember when you unveiled your bullish commodities thesis, you know, around the start of the new year or the end of 2020, you sort of had like a trifecta of reasons that you thought were going to drive the market. And one was the idea of this redistribution of demand. So basically, you know, people getting stimulus checks and going out and buying new things and buying steak dinners and things like that. And the second one was I think the structural underinvestment in traditional energy like oil, and then the third was this idea of supply chain and stockpiling. So people just sort of trying to build up their own energy independence or resiliency. And I’m curious, just looking back at that framework, is there a particular thing that has surprised you or stood out? Like, is there one leg of that sort of tripod analysis that has really caused the big spike that we’re seeing?

Jeff:

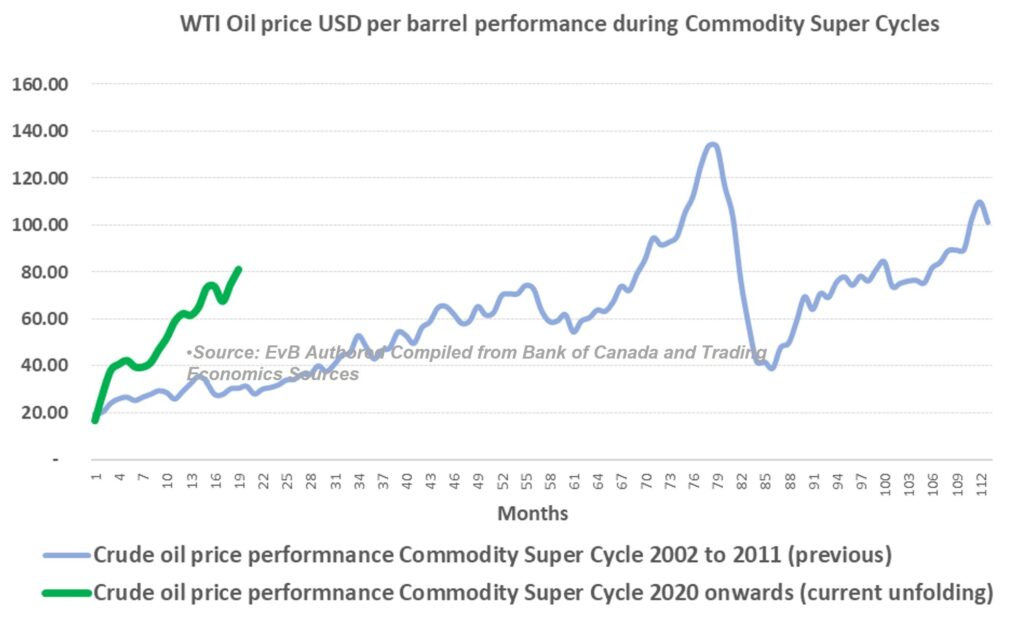

Actually all three are far more important than what we ever envisioned. And I actually want to go with the one that predates Covid. And the one that predates Covid is the underinvestment thesis. The theme that we termed it is the ‘revenge of the old economy.’ Put bluntly, poor returns in the old economy saw capital redirected away from the old economy and towards the new economy, basically taking from the Exxons of the world and given to the Netflixes of the world. And as a result, you starve the old economy of the capital base it needed to grow production and hence the problems we have today. So if it’s trucking in the U.S., which is old economy, chip manufacturers for autos, which is old economy, energy and gas in Europe or coal in China, they’re all the same story.

Now you can argue with the hydrocarbons, as you pointed out that the ESG factor, turbocharges this story. And it clearly has in places like Europe. But I want to emphasize at its core is that these companies have failed to deliver good returns over the last five to 10 years, and investors have had enough. And I like to point out, you know, we got a lot of investors back into the commodity and the old economy space. You know, when we were talking last January, but prices went up to $80 this summer on oil. And I remember it was late August — around August 28th — it was a Friday, oil had collapsed back down to $65. And these investors were going: ‘You lured us back in there. You said the coast was clear. We got in here and we just got completely hammered in terms of the volatility.’ They left. Then oil prices, where are they again? They’re back up to $83? There’s something inherent about the investments in here that make it difficult to attract capital.

It’s not going to be a smooth ride, you know, like it is in tech stocks where you just trend up. Instead, it’s going to be very volatile. So the bottom line, we’re sitting at $83, $84 a barrel oil today. And there’s no evidence of big increases in capex drilling, greenfield capex in metals or new acreage in agriculture. I can keep going down the list. So not only are the C-suites, the corporates, not spending on capex, but the investment dollars in this space is quite low. And as a result, if you get the investors to come back in this space, which we think could happen as we go into year-end, it could catapult the situation on relatively tight fundamentals that I started this discussion with. So I would say that’s the one, I want to point out.

But just quickly on the redistribution story that, that you bring up, the redistribution story is much [more] broad-based around the world than what we initially thought in way, if we think about, you know, in the U.S. when we were talking in January, could we have ever envisioned the $3.5 trillion U.S. human infrastructure fund? Um, absolutely. It was, I mean, this shows you how much larger these redistribution policies have become. Also, you know, the $1.9 trillion recovery act back in, you know, March, then we thought it was going to be $1.1 trillion. You know, it shows you just how much bigger these redistribution policies. China has its common prosperity, green leveling here in the UK. So it’s very — you know, you look at Germany’s government moving left, you know, Latin America’s moved left since we last talked. So bottom line is, you know, the redistribution policies are also bigger than what we thought. And then finally, just point on, you know, about the call. It de-globalization, I think to argue the trucking problem in the U.S. exemplifies the problems around de-globalization is because you have too much stuff being produced locally at home, in the us, which overwhelms the transportation, warehousing trucking, um, rail system, which has helped create some of the problems there. So why don’t we, you can think about United States exemplifies the problems with de-globalization Europe exemplifies the problems with decarbonization with what’s going on and it’s gas crisis. Anyway, that’s long answer to your question about all three.

Joe:

I mean, we want to hit all of these topics more, but let’s go a little bit more into the sort of like decarbonization, ESG stuff, because I think there are a lot of people who are like, ah, we told you so. You politicians had your visions of like a green economy, where we would all like power everything with windmills and solar panels and now look at the price we’re paying and maybe we won’t even be able to heat our homes. But the way you described it is a little bit, like, maybe some of that, but also like politics aside. A lot of these traditional fossil fuel investments were not great period. So how much is it sort of, as you say decarbonization policy that’s contributing to this revenge of the old economy versus decarbonization economics where people just weren’t making the investments because the numbers weren’t good?

Jeff:

Yeah. The, the bottom line is the returns in this sector were abysmal. And I don’t care if it is oil, gas…

Joe:

When you say this sector, you mean, just to be clear?

Jeff:

All fossil fuels. Oil prices were negative last year. You couldn’t create a more hostile environment, you know? So when you look at the investors that I try to get to come back in this space, they’re going, no, I’ve been there. I’ve done that. I know how painful this sector is. And so the way you could argue is ESG — the binding constraint, show me a great company with fantastic returns that’s not getting capital due to ESG. Right now, they don’t get returns because they’ve demonstrated a very difficult environment to generate returns on average. In fact, you know, you look it up, they’ve shrank down to two and a half percent of the S&P 500. To give you an idea, in the late seventies, they were running around 20%. So it’s a big shift here. And I think, you know, I spend time talking to many energy specialists and you get CIOs of these big asset managers on, going: ‘Hey, you know, I’ll listen to him once, but I’ve been there and done that before. And I’m just not that interested.’

And here’s a point when you look at the two thousands, that bull market. Prices spiked in 2003, but it wasn’t until 2006 that the capex began to flow. Why? Because they had a couple of years of really good returns and the investors felt really good about it. But I think, you know, the key point here is first and foremost, it is the revenge of the old economy and poor returns why the sector doesn’t get money. More recently you can say that, you know, it’s likely to be ESG. But I’m going to give you an example in Europe where it clearly is ESG. You know, the courts in Europe, the Hague ruled against Shell, made Shell liable for scope three emissions. That’s what the users of oil create. You know, that’s massive liability.

Yes, they’ll appeal it, but it’s going to be, you know, five, 10 years from now. I think the key point here is that with that kind of liability risk, nobody in their right mind is going to make large scale investments in places like the North Sea again, because they don’t want to be associated with that kind of liability. So it is beginning to bite, but you know, your standard ESG investors, and I do want to say they’ve raised the cost of capital and we’re going to find out — and this is where the ESG really comes into play — is we’re going to find out what price of oil do you need to get capital to flow? I like Scott Sheffield of Pioneer. He said a few weeks ago, he goes I don’t care if the oil price goes to a hundred dollars a barrel, I’m not going to drill. What’s going to make me drill? I need my stock price to double. And we’re going to find out at what price of oil these investors will start to buy these stocks again. You may be right, Joe. It may be that they’re just not going to buy it because of ESG concerns. I tend to think that’s not the case. There is a cost of capital associated with decarbonization and we’re going to find out what that cost is.

Tracy:

Just on the topic of oil. I mean, how much blame can you lay at OPEC for investor unwillingness to put money into stuff like U.S. shale? So, you know, there was always the sense that if shale flooded the market, then OPEC would react in some way and boost their own production and drive a bunch of the shale producers out of business. And then now, even as we see oil prices pressured higher, I mean, OPEC is still being pretty disciplined in terms of production. They haven’t said they’re going to ramp up output by that much. So I guess the question is like, what role does OPEC play in investors’ calculations?

Jeff:

The current OPEC, they got religion. They understand. They’ve been through a lot of pain. They couldn’t have a better business model than what they have today. They’re focused on balancing the market on a near term basis, keeping inventory low, keeping the forward curve in what we call a backwardation. So they’re focused on what they can control, which is the very near term balance. And then they create a credible threat that they will bring on capacity, bring investment on, which keeps the back end of the curve depressed. So they got what we call a backward -dated curve. Spot prices are high, backend prices are low. But to get to that level, to get to this great discipline and I would argue, you know, a great policy structure which makes sense given how much share they control in the market, it was a big policy mistake. And that policy from November 16 till March of 2020 was utterly disastrous and created a lot of problems we have today.

They didn’t, they’re not a monopoly, they’re not like the Federal Reserve where they have a hundred percent market share over the dollar. They don’t have, they have maybe a, you know, put them all together, a 33 to 40% market share over the barrels. And so for their ability to cut back production and maintain prices at $60 to $65 was always invariably unstable. And the investors that got lured into investing in the sector based upon that $60 price had a high probability of having the problems that they ran into in late ‘19 and, you know, 2020. But I do want to say, I think they’ve learned from those mistakes, you know, the new group of energy ministers in particular, I think they understand all of these issues. And so I’d argue they’re doing a fantastic job, they’re really sticking to what they’re supposed to do. And what they’re really good at is managing near-term imbalances in the market and focusing on providing capacity on a longer-term basis, which has left the forward curve in a backwardation, which makes it really difficult for the EMP producers to hedge. Why? Because prices are a huge discount on the back end, relative to where they are on spot.

Joe:

So before we move off of oil, I want to talk about U.S. oil a little bit more. And, you know, I’m thinking back to like 2014, 2015, the good old years, and there was this perception, or there was this characterization of U.S. shale as the swing producer that sort of kept a lid on prices because as soon as prices would rise a little bit, they could quickly ramp up production and that would bring prices down. And part of it was a rates story maybe, part of it was the technology story. What is the status of U.S. production now? And why is it not having that effect of being able to ramp up aggressively and sort of smoothly? I mean, I think there is some increase in the rig counts, but as you said, not that much. So why are we not seeing something greater out of the U.S. as a stabilizing force?

Jeff:

For one back then, the companies were rewarded on volumetric growth, not on return on equity. The investors paid a terrible price for that period. You look at the industry, you know, it destroyed a lot of wealth, like 10 to 20 cents on every single dollar. I think the number is actually closer to 30 cents on every dollar.

Joe:

So basically that aggressive supply response was just a mistake? Like it was just a bad, it was just, in retrospect, it turned out to be a bad approach to business?

Jeff:

Because they were operating at like 105 to 115% of cashflow. So, you know, what they were doing is they were basically growing volumes on the expectation of future returns. But obviously when you grew all those volumes, you would get crushed on the backend in terms of what was being delivered. And so the focus left being a focus on ROE, and instead being a focus on growth. Today, the focus is on ROE. They want to get those returns on equity up. And by the way, the investors who own this company, they want their money back. You know, the OPEC ministers want their money. Everybody wants their money back from the disastrous experience over the course of the last five to seven years. So at this point, you know, you look at why aren’t they drilling because for the first time in nearly a decade, and in fact, you probably have to go back, yeah, you got to go back to ’07, ‘08, that these companies are finally getting free cashflow going up.

They’re not overspending. They have returns moving higher. And so now they’re getting rewarded on return on equity as opposed to growth. And it’s going to be a while. Everybody wants to be made whole, and then they’re going to get the green light to go out and invest. That’s kind of the point. I think Scott Sheffield got it right. The focus here is not on the dollar price of oil, but where is their stock price and their access to capital? Now here comes the whole ESG issue, which means that that hurdle rate is going to be higher and higher before that capital’s going to come in and make that stock price go higher. I tend to think there’s always somebody in the world out there who’s going to buy this, which is why, when you look at the, you know, the investors that do pursue, you know, these ESG strategies, it’s going to be difficult because there’s going to be somebody out there in the world that’s not restricted around these, that’s is going to go out and make these investments, which I think, you know, makes it, you know, it’s not a level playing field right now.

Tracy:

Since you brought up ESG, I guess the obvious question here, the big question is what does all this mean for ESG or green investment? Do we start to see a backlash to green investing and do investors, you know, maybe start pulling out capital or put less capital in or divert some capital to, you know, older fossil fuel energy and things like that?

Jeff:

Well, I have a couple points on that. One divestitures never solved any problem. And when we think about, you know, with ESG in particular, it came about originally because the Europeans were getting frustrated that the Americans and Chinese were not doing anything on the policy side, but the problem why the investors drifted into the policymaker lane is a policy makers weren’t doing their job. And when we think about what job they need to do, they need to create, you know, rules around decarbonization that allow operators to operate around and gives investors the rules of the road in which to invest around. And that’s kind of the problem is that there’s this nether world that’s occurring. And they got these investors just trying to invest in, or policymakers trying to make these investments in things that they don’t really understand. And I think it’s a really risky environment that we’re in. And I think what’s going on in Europe is a testament to the misallocation of capital that can occur in this environment in where you’re [inaudible] markets dictate and policymakers dictate what the rules of the road are and what, you know, investing around those rules of those road.

Tracy:

Hmmm. Just on one of those points there, I mean, the point about the role of the government there is well taken and that’s been of the major criticisms of ESG that they’re trying to fulfill something that should actually be done by governments and through new laws and things like that. But there’s also this sort of foundational debate in ESG about whether or not it should be investors engaging with companies to make them change their behavior. So you care about the environment you’re invested in Exxon or Shell or whoever, and you try to encourage them to change their behavior by actually being invested in having a relationship with the company. Or do you ignore them altogether and invest only in companies that are doing renewable energy that have divested all the old, traditional, dirty stuff, and you try to increase the cost of capital for anyone who is basically in that old energy space. I don’t know what my question is here, but like, I guess it’s, how do you think, like ESG should function? Like what is ESG trying to do?

Jeff:

I think, you know, your Exxon example is spot on. It’s going in there and helping the situation and trying to find the solution is the right answer. It’s the divesture knee jerk reaction that’s the dangerous one. And I want to really distinguish between that. So when we think about, you know, ESG, that, you know, preserves the market signaling, then it’s working great. It’s there where you go, okay, anything that’s hydrocarbon is bad. Let’s shut down the investment. Because bottom line, India should not have three days of coal stocks left right now. Just think about that — three days of coal stocks. And if all of a sudden you had a major disruption India would be out of power in three days, that’s a dangerous place to be for one of the largest, most populous countries in the world.

Joe:

Let’s talk about some of this sort of like ongoing sort of mechanical disruption issues that we’re seeing. And I want to actually focus in on what we’re seeing in China, because it seems to be, there’s a number of moving parts, Tracy and you both talked about that earlier. Overall, what is your take? Let’s start big picture and then maybe zoom in on specific commodities. But overall, what’s your take on sort of like the Chinese energy picture? Cause it seems like very extraordinary and unusual.

Jeff:

Well, you know, it boils down to shuttering of very toxic coal mines. I like to point out what China’s going through today is very similar to what the U.S. did in the seventies when, you know, creation of superfund sites. So it shut these down, these things were very toxic. Then you don’t have the investment in coal globally. And then you have a foreign policy spat between Australia and China. So you put it all together, the access to coal dropped tremendously … By the way, this is all stems from the fact that these supply constraints were there. It took that post-Covid surge in demand that exposed it all across, you know, metals, oil, gas, coal, trucking, you know, whatever, pick your industry. It exposed them all in the old economy.

And it had happened to be particularly acute in coal in China. So then what happened is then they had to replace the lost coal with gas. So they started to hoover up the world’s LNG supplies. Then they started replacing it more recently with oil. Um, and that’s, what’s helped create the big deficit in the oil and the bid in oil. So the bottom line is, you know, you put it together, the situation is dire enough that even our economists have trimmed fourth quarter GDP to being flat with three quarter and taken down first quarter of ‘22. Now there’s investments in coal in Mongolia, and then potential increase in exports of 300,000 tons that many people point to that means this problem goes away next year. It eases the problem. What about further growth rates in GDP and more activity? It just puts more stress on the system.

That’s why we like to argue this thing’s a supercycle, meaning that, and then think about how much stress you put into aluminum, zinc and all these other industries where you’ve had to shut down smelter. So if you want to really think about the chain reaction here, some people kind of simplify the world. It starts in China, coal in China, and then that creates tightness in gas that created the problems in Europe, Europe substitutes into oil, creating the problem in oil. You’ve shut down the (aluminum) smelters, the zinc smelters, you know, so a lot of people say, you know, that the ground zero of those problems really was coal in China. So I do want to say the situation in China is very dire, but it’s just one part of the world that can create a solution to it rather quickly and they’re trying to with investments in Mongolia.

But I want to be careful about restarting a lot of that shuttered coal. For those of us that are Americans and know what a superfund site is in the U.S., restarting these facilities is going to be a lot more difficult, a lot more expensive than I think what people think it will be. So you really got to focus on the new, more cleaner, sophisticated coal, in some of these mines in places like Mongolia. So bottom line, it’s going to be tight over the next three to six months, but once you get that Mongolian coal up and running, the situation should ease, but no way does it solve it.

Joe:

You mentioned it briefly, but you know, when we talk about important global commodities, obviously the first one that comes to mind is probably oil. And I don’t know, maybe natural gas, aluminum prices [are at a] 13-year high in China. And of course, aluminum is used in all kinds of just everyday items. So if we’re thinking about how commodities bleed into sort of normal inflation, that seems like an important one to focus on. Can you walk through a little bit more about the economics of aluminum in China right now, and what you see going on sort of like putting this inexorable upward price pressure there?

Jeff:

Aluminum is a unique commodity, it’s the climate-change paradox. You need it to solve climate change, but it creates a lot of emissions in the production of it. So, you know, it does two of the same. And so when we think about the situation in China right now, if you’re operating on a call it a carbon budget, you know, you’re allotted this amount of carbon production for your economy. One of the most polluting, you know, commodities. In fact, it is the most polluting commodity to produce is aluminum. You’re not going to want to produce it, it’s getting the first thing you shut down. Think about what really is aluminum. It is solid energy. You just take alumina and electricity. You put the two together, and now you’ve got, you know, a solid piece of metal there. So if you’re trying to conserve energy, conserve, you know, how much carbon you’re admitting, the first thing you’re going to pull the lever on is going to be aluminum, which is why you look at, you know, you know, China’s cut 2 million metric tons of capacity, you know, that and about a 50 million metric ton market.

So it’s sizable in terms of what they’ve taken out on top of, you know, that stuff that’s already been taken out elsewhere in the world. So that’s really at the core of what’s driving this. But I do want to go back to the point about cost push inflation, that commodities are being driven by cost push inflation. There is zero evidence of it. It’s always demand pull in the sense that, you know, demand is strong across every single one of these commodities, services and everything else. And it’s demand pulling everything along against the supply constraints that creates the upward pressure on prices. It’s not the input costs accelerating that’s driving up the cost and other parts of the industry, but you think about how did it, you know, aluminum, how does it create tightness in other markets? Because once you lose a supply, let’s think about it, it starts with coal. Tightness in coal.

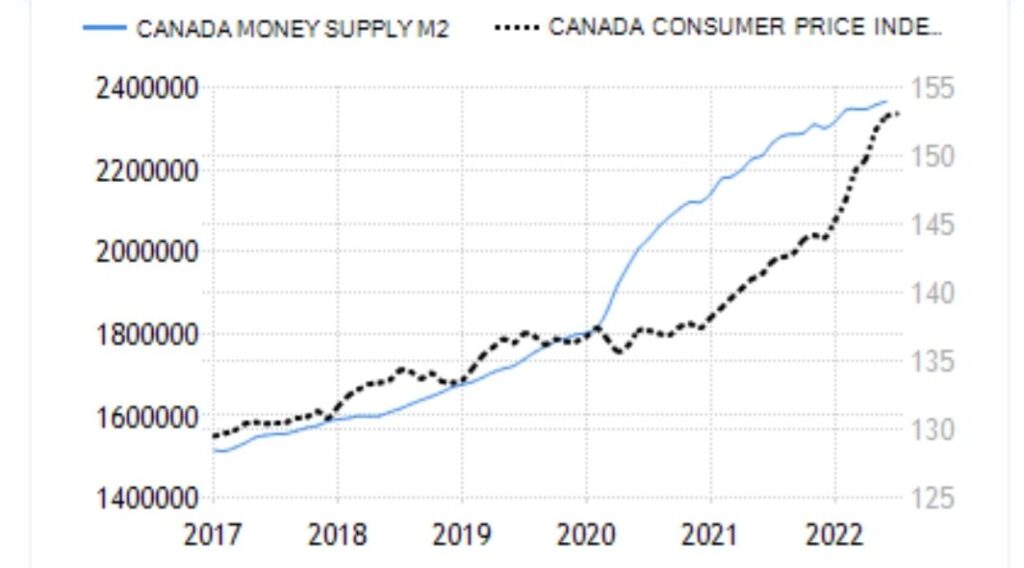

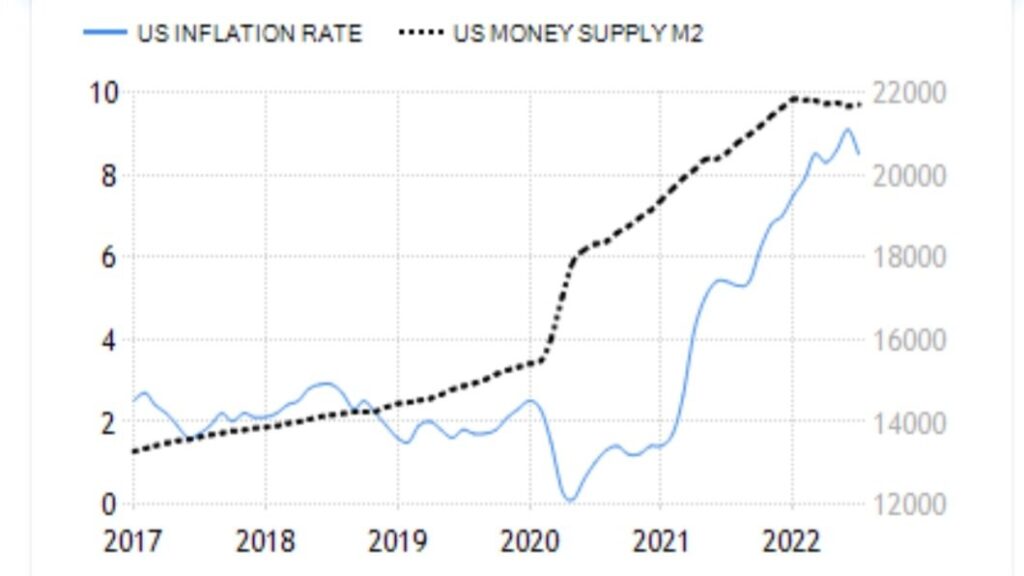

It’s not that the coal price led to higher aluminum prices. What it was, was a lack of coal led to a shutdown of aluminum smelting and against strong demand that drove up the price of aluminum, which then feeds into more demand for copper as a substitute against aluminum. So, you know, you can think about it as being, you know, the supply chain, you know, working along that way. So it’s not that that the cost of, you know, energy is driving the cost of everything. It’s demand pulling everything along. And when you think about it that way, you know, that’s how you get broad-based inflation because it’s not just isolated. Cause think about it, if it’s isolated in one market, let’s say oil prices, that’s a relative price move. And if you think about, if money supply stays the same, the price of oil goes up. Then the price of everything else has to go down because there’s a net constraint with money supply. But if you think about it, demand is pulling everything along, money supply is growing along with it. Then the price of everything starts to grow as opposed to being a supply shock being relative price moving away.

Tracy:

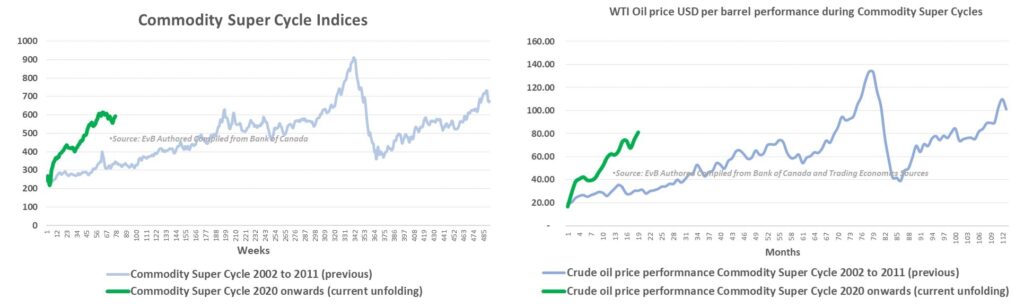

You touched on this earlier, but what’s the difference between a bull market in commodities versus a supercycle? And like, I, I sometimes get the sense that like commodities experts are very sensitive on this particular topic mostly because I had an argument earlier in the year about whether or not what we were seeing was a commodities boom, or the start of a supercycle. And people got very, very pedantic, but like, what is the difference? And which one are we looking at at the moment?

Jeff:

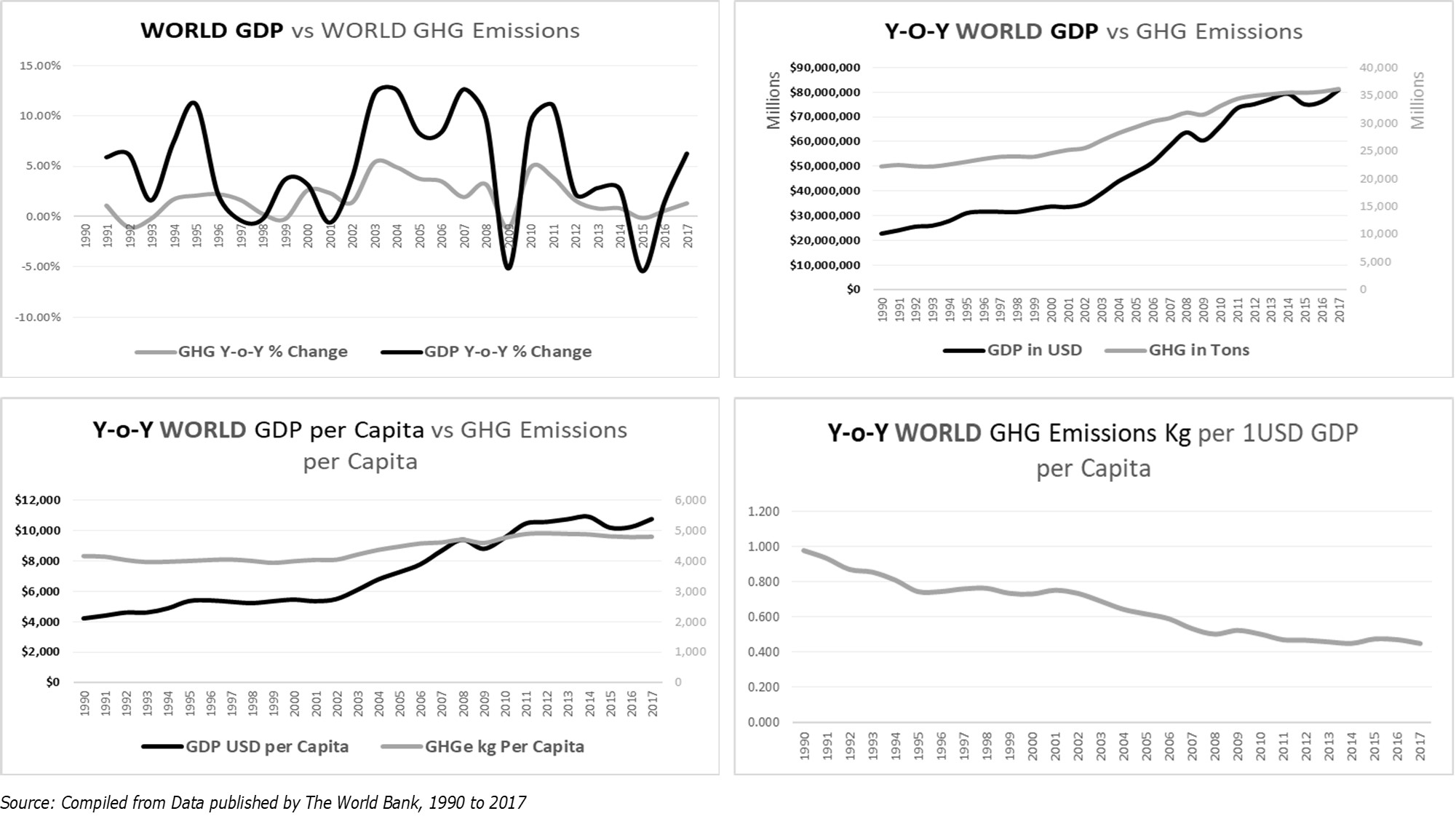

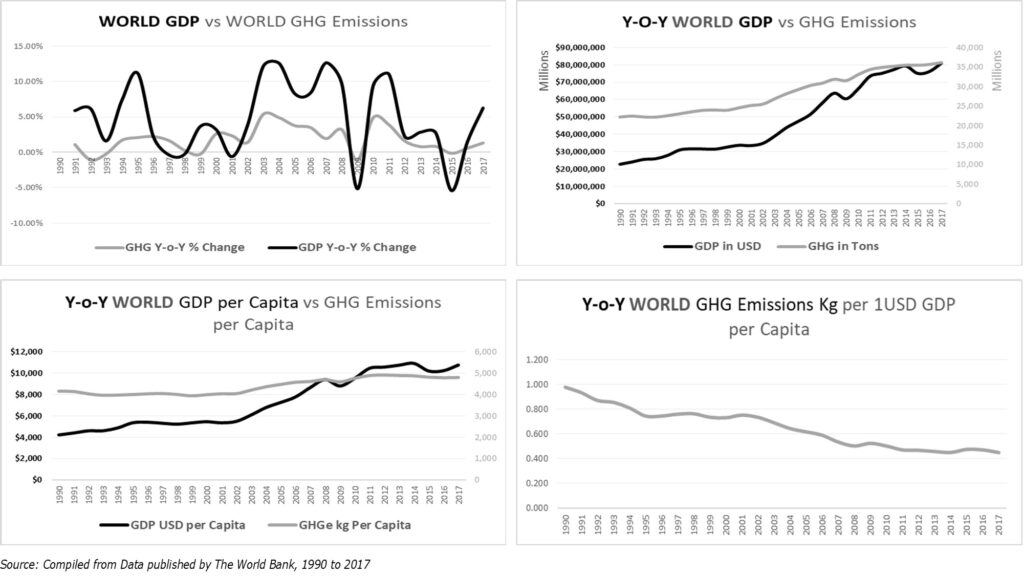

We’re looking at a commodities supercycle and it goes back to this demand demand story. It needs a structural rise in demand. I can get a bull market in oil driven by a supply shock in Saudi Arabia, but that’s not a supercycle. A supercycle is driven by a structural rise in demand. And why do we have a structural rise in demand? And give me a minute here because I really want to explain this point because I think it’s critical to understanding the difference between physical markets and financial markets. And we think of physical markets like oil or aluminum, they’re what we call volumetric markets. How do you determine if you’re bullish oil? The volume of demand versus the volume of supply. If demand is above supply you’re bullish, no dollars enter into the equation, no growth rates, nothing like that. So physical markets is driven by volume.

Now what are financial markets and GDP, they’re all driven by dollars. How many dollars do you pump into those markets? And it determines whether or not they’re bullish or not. You know, so no volume enters into a financial market. Think about equity. You quote it in billions of dollars, or GDP, you quote it in trillions of dollars. Volume doesn’t enter. So let me summarize. Physical market’s driven by volume ,financial markets and GDP driven by dollars. Now let me ask you the following. What do the world’s rich control? Dollars. They control wealth and income. Can [the] rich create financial inflation? Absolutely. Yes. Can they create GDP? Absolutely. Yes. Can they create physical good inflation? Numerically impossible. There’s not enough of them. It’s a volumetric game. And so only the world’s low income group can create inflation and commodity bull markets. And there is no exception to that. You cannot find me an exception.

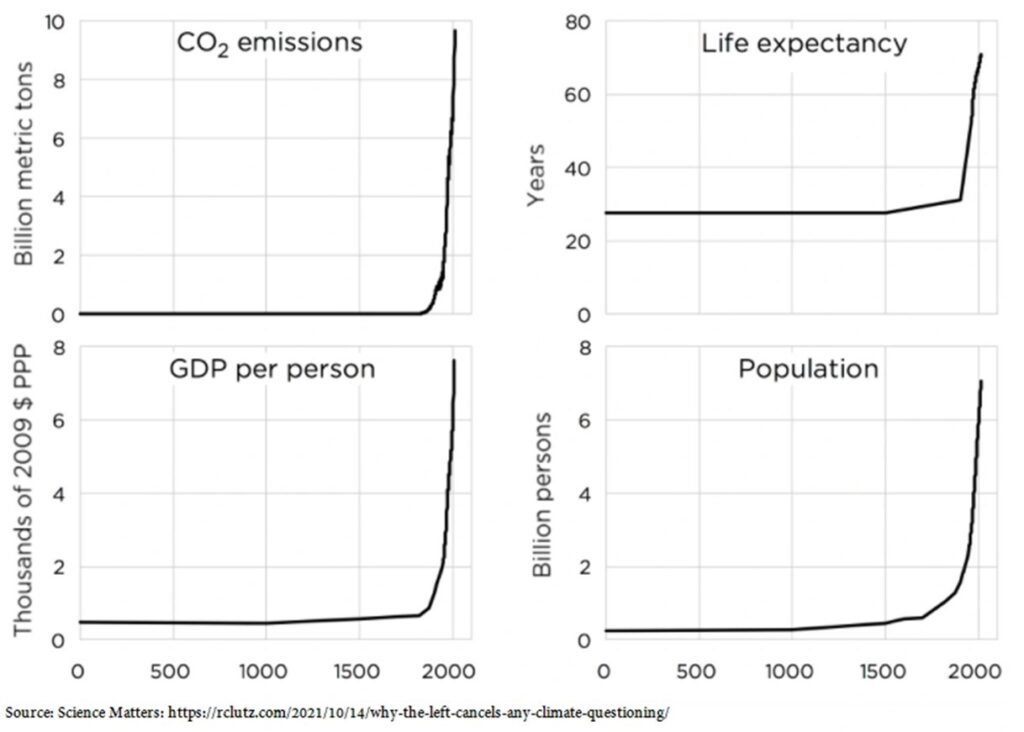

Every commodity supercycle is driven by low income groups, as well as every bout of inflation. In fact, you know, let’s start with the seventies. It was LBJ’s war on poverty. The 2000s, when China was admitted to the WTO, it was a gigantic wealth transfer, rich Americans and rich Europeans to low income rural Chinese — 400 million of them. There was your volume, it created inflation in China and a commodity bull market. You know, the inflationary episodes in Latin America tied to populist policy. The list goes down and on. So you come to the conclusion that inflation and commodity bull markets are directly tied to populous policies. And I can’t find an exception to that. So if we argue that we’re in an environment in which there’s, you know, great focus on low income groups and even think about green capex as Joe Biden says green capex creates jobs. As Boris Johnson here in the UK says, he calls it green leveling, spending on green capex to create jobs.

So everywhere we look, even the green capex is focused on lower income groups. And as a result, then we look across the demand levels. You know, gasoline barrels were at an all time high this summer, and I can go across the board, the volumes, just look at the level of demand of durable goods and everything like that. It’s off the charts. So that’s the reason why I think we’re in a commodity supercycle. It’s not because of anything else other than that simple observation that the volumetric demand growth we see right now and going forward is not just a, you know, it’s something that’s hitting all the markets simultaneously. And that’s really what is at the core of a supercycle. So Saudi losing production can create a bull market in oil, but that’s not a supercycle. Was that clear?

Joe:

Yeah, that was fantastic. So I guess like, you know, I know we just have a couple of minutes left here, but, you know, like I said, we talked to you in January. I felt like you nailed the call and then some. We’re in the supercycle as you characterize it. I don’t know commodities, it’s always a cliché, innings, so to speak, but what are we going to be talking about with you in nine months when we rebook you and how much longer is this going to be going for? What’s going to happen in the future. What’s your crystal ball say?

Jeff:

We’re going to be pricing scarcity at that point in time, across oil, metals and everything at that point in time. And when we think about, you know, the transitory nature of these events is that when the system is so strained, like it is right now, it just takes a small little problem to create a big upward movement in price. So you think about what Europe was created by. It was created by the wind quit blowing. The market had to replace that wind power generation with natural gas. And there was no gas there and a small event like the wind quitting blowing, created a massive price spike … Before you’d have to draw something out of the tails to get a problem. Today, you just draw something in the middle of the distribution and you get a problem.

Which means that these transient events are going to be, they’re higher probability and more frequent in nature. So there becomes a persistency to the transitory events. That’s what scarcity pricing is all about. It’s not like you’re going to get a big upward trend in prices, but you’re gonna continue to get, you know, price spikes. So, you know, I think if you brought me back in six months, I think that’s going to be the highest pain point. By the time we look at nine months, you have a much higher probability of the system trying to find solutions to it. So three to six months, I think that’s going to be your max pain point. On oil, we have a $90 target but I want to emphasize lots of upside risks to that. We look out to next year, we’re $11 to $12,000 a ton on copper, but you know, a lot of upside risk to that.

But the real upside risk I’d argue probably happens in that first quarter of next year. Hopefully when we meet nine months from now, we can say, Hey, you know, we see drilling in the U.S. We see, Iran deal has come, you know, there’s a higher probability of getting an Iran deal, the system begins to ease, which is why we see prices moving back into that $80, $85, at the nine month horizon. So if we meet six months from now, I think there’s going to be peak scarcity pricing, and nine months from then to a year, much higher probability that we’ve found some type of, at least, near-term solution.

Joe:

But max pain still coming…

Jeff:

Max pain probably coming in the next next three months, if not sooner.

Joe:

Max pain still coming. Jeff Currie. Thank you so much, always great to chat with you, a real treat. And like I said, we’ll have you in a six or nine months back, and we’ll see if we’re at truly max pain.

Jeff:

Well, thanks for having me.

Tracy:

Thanks Jeff, appreciate it.

Joe:

Take care, Jeff. It’s always a treat talking to Jeff. I just feel like I get like such a big, such a useful, big picture perspective talking to him.

Tracy:

Totally. And I mean, I feel like I’m a little bit biased because, you know, I was a capital markets reporter for a long time, I like writing about things like corporate bonds, but I remember writing a lot about the shale boom in the U.S. as a capital markets story. And I think Jeff did a fantastic job of like drawing that connection once again. You’re not going to get higher oil production and less investors feel comfortable putting money into the company and the company feels comfortable actually putting that money to work in terms of investment and expanding production. And we’re not quite at that point.

Joe:

You know what, I love that point because there is this sort of very clichéd [thing], which I’ve always hated, where like the stock market isn’t the economy. Actually, the stock market is a very important part of the economy. And sometimes maybe it reflects the economy, but sometimes it very much, sometimes it doesn’t reflect the economy, but sometimes it drives the economy. And so when you have a CEO, as he was pointing out, and I want to go find that transcript where he’s like, you know, the determinant now of how much U.S. oil will ramp, it’s actually the stock market itself and the sort of return expectations of investors and having learned the lesson of the sort of like 2010s that pure volume is not a great long-term return on investment is super fascinating to me. It’s like, we’ll drill more when the stock price goes up is sort of like the opposite of how people think like, oh, the stock market is just a mirror to what’s happening in the real economy. And that case is clearly a driver.

Tracy:

Oh, totally. I mean capital markets matter. And this is a really good example of that. The other thing I would say that I really appreciated hearing was his differentiation of, you know, a commodities bull market. The idea of commodities just going up versus a commodity supercycle. And this idea that ultimately a supercycle is something that’s going to come down to physical volume and scale. And so that scale has to come from somewhere and he sort of pinpointed the idea of scale coming from surging demand from the sort of, what did he say, lower income class.

Joe:

Yeah, the redistributionary impulse. For sure.

Tracy:

Which makes a lot of sense, you know, it’s about scale. And so it kind of has to be about consumption from like the biggest proportion of the population as possible.

Joe:

So many interesting points. You know, his point about how normally like, you know, a few days without wind in the UK wouldn’t be a big deal, but this time, because of the tightness of the market, so many comparisons between what’s going on in logistics. Really great getting his perspective on aluminum. Just it is a real treat to talk with Jeff. And again, we got to get them back on it like six or nine months.

Tracy:

Yeah. We’ll make this like every nine months type of event. I think that would be good. Ok, shall we leave it?

Joe:

There? Let’s leave it there.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/AOGWERLKHNMTVE2KP3SFAUGBGA.JPG)